The Zoo Metaphor

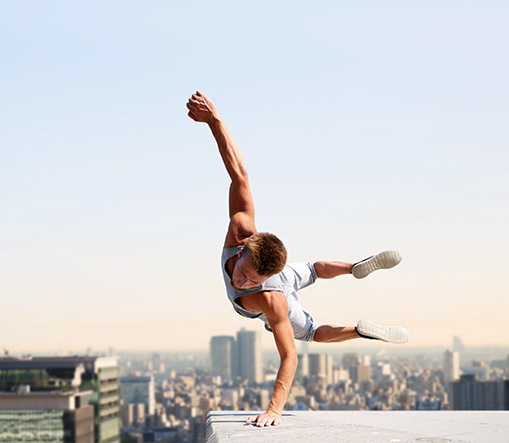

Imagine a lion in a well-designed zoo enclosure. The goal of the zoo isn’t to perfectly recreate the Serengeti or explain captivity to the lion. Instead, the enclosure provides an environment where the lion behaves naturally – hunting, sleeping, roaming according to its instincts.

When researchers observe the lion, they focus on its behavior, not anatomy. They don’t dissect it or simulate hunting in a lab. They watch what the lion actually does in a realistic, constrained environment.

This is how software should be tested.

A well-designed test environment doesn’t teach the application it’s under test. It provides real infrastructure in a controlled setting and lets the system behave naturally. The application connects to a database, executes queries, commits transactions, and handles errors exactly as it would in production. It doesn’t know the difference.

This is what I call Zoo Testing.

Once an application is “zoo-ready,” it becomes remarkably portable. Swap the enclosure to match your needs: development with a single container, CI with parallelized tests, load testing with traffic bombardment. Same code everywhere.

The Problem We’re Solving

When we test software, we often change its environment in ways that fundamentally alter behavior. Different databases, different configuration, sometimes different code. We convince ourselves these tests say something meaningful about production behavior.

They often don’t.

An application should run the same code in tests and production, against infrastructure that enforces the same constraints and failure modes. If it knows it’s being tested, we’re no longer observing real behavior – only a simulation.

A Concrete Example

I recently spent an extended time working on a MongoDB Atlas Search system – complex queries, stored fields, geospatial scoring. Throughout development, I used testcontainers and tested exclusively through public interfaces. I didn’t deploy once during that period.

When finally deployed to the client environment against real data, it worked without surprises. No emergency fixes, no environment-specific bugs.

The test environment had already caught issues mocks would have missed: unique constraint violations, case-sensitive string comparisons that differ between H2 and Postgres, index behaviors that can’t be anticipated when telling mocks what to return.

This wasn’t luck. This was running the same code against infrastructure that behaved like the real thing.

I’ve applied this approach across multiple projects and languages. It consistently catches more real bugs, makes refactoring safer, and gives genuine confidence in what we’re shipping.

What Zoo Testing Actually Entails

Zoo Testing changes what we consider a meaningful test. Tests interact with the application only through the same interfaces real users or systems use. If users create resources via HTTP, tests make HTTP requests. If data comes from a queue, tests publish to that queue. Internal classes and repositories are implementation details, not test targets.

I’ve built microservices where tests only verify edge behavior: does it produce the right message to the right queue? Does it call the expected HTTP endpoint? Are the changes the test made observable to the user? Internal implementation is irrelevant. What matters is correct external behavior.

The goal: verify observable behavior from outside, not internal interactions inside. We observe what the lion does, not its internal organs or neural pathways.

Building the Zoo

Modern tooling makes this practical:

Testcontainers run real infrastructure in Docker – PostgreSQL, MongoDB, Kafka, Redis, Elasticsearch. Not simulations – the same engines that run in production, enforcing the same transaction rules, constraints, and query semantics.

LocalStack provides local AWS services – S3, SQS, DynamoDB, Lambda – using the same APIs as the cloud.

WireMock creates real HTTP servers with actual serialization, status codes, and timeout behavior.

The application is unaware it’s being tested. It simply runs.

These catch bugs mocks never would: timezone parsing errors, H2-to-Postgres SQL dialect differences, concurrent transaction deadlocks, constraint violations in-memory databases ignore, serialization mismatches.

Developer experience is excellent: Once you have Docker installed, a simple command runs all tests. No complex setup, no environment variables, no “works on my machine” issues. Clone, run, done.

The Testing Diamond

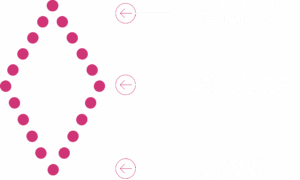

The traditional testing pyramid advocates a large base of unit tests, fewer integration tests, and minimal end-to-end tests. This made sense when integration tests were prohibitively slow and expensive to maintain.

With containerized infrastructure and modern CI, that trade-off has shifted. A better model is a testing diamond:

Most testing effort goes to integration tests hitting real infrastructure. Unit tests focus on pure functions and complex logic. End-to-end tests cover critical user paths.

Integration tests provide: real parsing with edge cases, enforced constraints, correct transaction behavior, actual query performance.

This doesn’t eliminate unit testing. It repositions it.

Code Structure: Pure Logic and Side Effects

Zoo Testing requires clear separation between pure logic and side effects.

Pure logic: deterministic computation, no external impact. Perfect for unit tests – fast, focused, no infrastructure or mocking needed.

Side effects: database writes, messages, API calls. Cannot be meaningfully verified with mocks. A mock confirms a method was called, not that the effect occurred. That’s checking if you put a letter in the mailbox, not verifying it arrived.

Side effects must be tested by observing outcomes in real systems. Write to real databases, publish to real queues, make real HTTP calls.

Pure logic in its own class, testable without infrastructure. Side effects at edges, verified by observing their effects in real systems.

Why Extensive Mocking Is a Code Smell

Mocking libraries – like Mockito in Java, unittest.mock in Python or gomock in Go – let you create fake objects that simulate dependencies without actually calling them.

Extensive mocking indicates tests focused on internal mechanics rather than external behavior. Remember the lion: observe real behavior in a real environment, not a cardboard cutout of the animal placed in the lab.

Testing Assumptions, Not Reality

Mocks test your assumptions about dependency behavior, not actual behavior.

You test: method calls, parameter verification, invocation counts.

You don’t verify: SQL works against real engines, JSON deserializes correctly, transactions behave properly, constraints are enforced.

You’re testing imagination, not reality. Studying the cardboard cutout, not the real animal.

Implementation Coupling

Mock tests encode implementation assumptions: which methods, what order, which parameters. These are fragile.

You’ve contracted the implementation, not the behavior. Refactoring for performance or introducing caching breaks tests even when behavior is correct.

I experienced this directly on a Spring Data Neo4j project. When we upgraded the SDN framework, our mock tests became obstacles. They validated “did we call the right repository method” instead of “does the query return correct data.” False negatives from implementation coupling. We had to discard them – they provided no value.

Real systems are judged by effects: user created? Email sent? Data persisted? Zoo Testing observes what actually happens.

Mocks bypass real-world failure constraints: schemas, transaction isolation, serialization rules, protocol semantics. Fast but shallow confidence.

Zoo Testing provides slower but deeper feedback, validating the system as it exists.

When You Think You Need Mocks

Testing pure functions? Move logic to separate classes, test with inputs/outputs.

Testing side effects? Use real infrastructure. Build the zoo.

Exceptions? Time manipulation (testing date calculations without waiting), extreme failures, legacy constraints – mock sparingly.

Frequent mocking means: code structured wrong (separate pure logic), or don’t know the alternatives (LocalStack, WireMock, testcontainers).

Addressing Objections

“Too slow!”

Postgres starts in 2-3 seconds. Use singleton containers – cost amortizes. Long-living containers between runs eliminate startup entirely. Parallelize across cores or CI instances. Partial parallelization helps, and catches concurrency bugs mocks never would.

Tests might take longer, but provide real confidence, not false confidence.

“No LocalStack equivalent?”

Azure lacks good local equivalents for some of its crucial services. Other providers also have gaps. Use testcontainers for databases/queues, accept mocks for cloud services, or hit test accounts. Real constraint, but typically small surface area.

“Harder debugging?”

Yes – more surface area when tests fail. But you’re finding real bugs: broken SQL, violated constraints, race conditions. Pay a higher price for a better value. Would you rather debug passing unit tests while production fails, or catch actual bugs before deployment?

Limitations

Zoo Testing isn’t universal. Some animals don’t belong in zoos:

- Time-dependent behavior – Testing date calculations or time-based logic without manipulating clocks

- Extreme failure simulation – Datacenter fires, specific timeout patterns

- Expensive operations – ML inference taking minutes, gigabyte processing

- Legacy constraints – Impractical rewrites

- Missing containerized alternatives – Cloud services, proprietary systems, mainframes

These are legitimate exceptions, but represent a minority of what most applications do. Where realistic environments can be provided, observing real behavior remains most reliable.

The Result

When applications run the same code in tests and production, interacting with infrastructure that behaves like the real thing, testing becomes observation rather than speculation.

Fewer surprises. Safer refactoring. Greater confidence.

I’ve lifted applications into different environments for load testing. Because they were zoo-ready, I swapped the enclosure, applied heavier infrastructure and traffic bombardment, and observed behavior under load. No modifications needed – already portable across zoo types.

Build a realistic environment. Put your application inside. Watch how it behaves.

That is the essence of Zoo Testing.